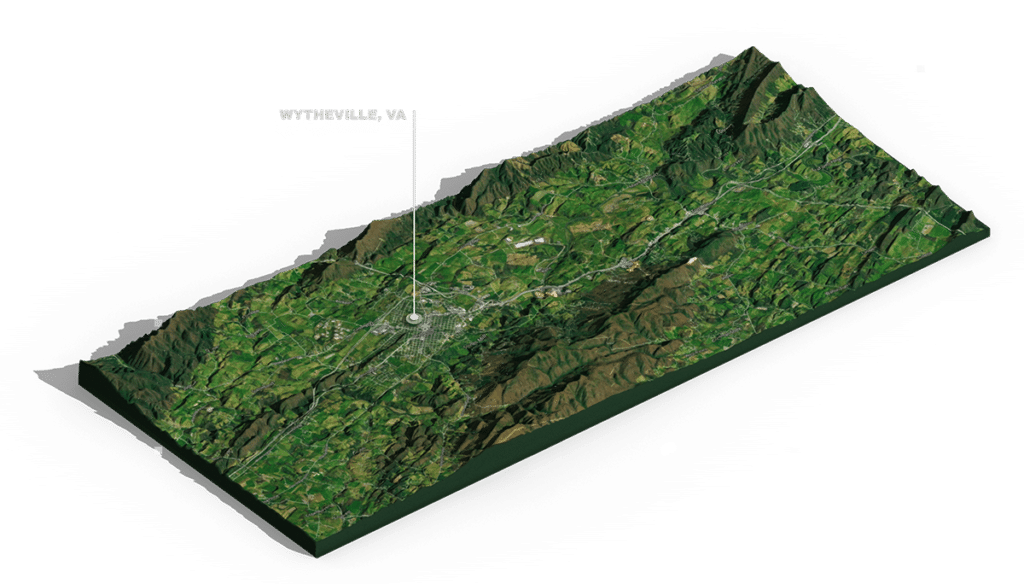

Somewhere along the line of history woven into the myth of an expanding America, there were two Wythevilles, until fate split them apart. One was sent into impermanence, now long since gone. The other settled discreet-like into the valleys of Appalachia, nestled between the crook of a rushing southbound I-71 and its East-West sibling, I-81, itself scorching a swath to the Atlantic seaboard, rarely looking back.

The Wytheville fate deemed obsolete was agrarian in origin: generations spanning generations possessed of small family farms since the county’s founding in 1789. The Wytheville that remains is cornered by interstates and with it, all the corporate and commercial traffic they bring: Best Westerns, McDonald's, Subways, a Starbucks. It’s a sea of low-wage work providing the barest of minimums. So minimum that the word “provide” hardly seems fair.

How did we get here? Was it by car? By rail? By the inevitability of time and opportunity? Is it the ambivalent hand of fate? The likely culprit is a combination of it all, each contribution unpredictable yet meticulously constructed as the roads that now spidered the land.

How did we get here? Was it by car? By rail? By the inevitability of time and opportunity? Is it the ambivalent hand of fate? The likely culprit is a combination of it all, each contribution unpredictable yet meticulously constructed as the roads that now spidered the land.

In many ways, none of it matters. The speculation at least. It’s the hand that Wytheville has been dealt. And somewhere in that hand – somewhere among the injustice and inequity, in and around the youth leaving for cities beyond, between the bottling plants, and above the grinding boom of semi-trailers – there exists kindness and reciprocity, respect and charity, neighbors providing for neighbors, all in equal parts. The list goes on. But space is limited. So we’ll just focus on The Open Door Cafe.

So we’ll just focus on The Open Door Cafe.

"Our Americorp aide came around the corner and asked: has anyone ever heard of the one world everybody eats model of serving food?"

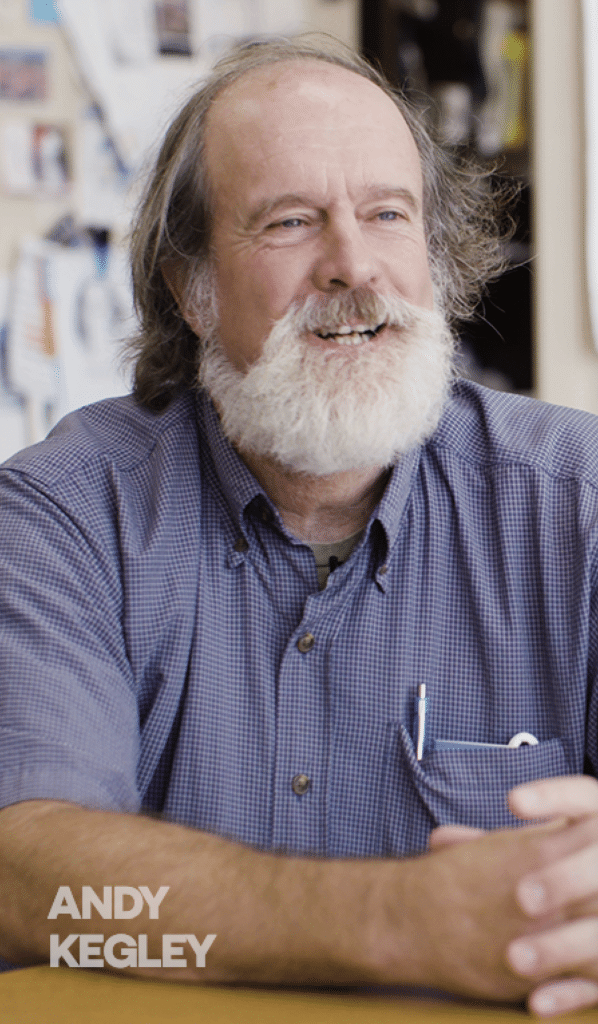

–Andy Kegley

Amidst the long transition to a modern interstate town, Hope Ministry sprang up, going on 30 years now. Andy Kegley is the Executive Director. For months he had led the process to raise enough money to attempt Wytheville’s first pay-what-you-can-model restaurant, hoping to notch just one arrow in the growing battle to address food insecurity in the area. The money came in slowly but kindly, primarily in the form of grants and donations. It was still coming in as they wondered: where do we put this thing? And, perhaps more importantly: would it work?

"Pretty quickly we had raised about $500,000 to support this idea of a community food kitchen into a pay what you can restaurant and we were searching the community where to put this."

–Andy Kegley

The tire shop was closed and boarded up, a for sale sign out front. Andy saw it one day walking out the door of Hope’s offices. It was right across the drive. Hope Ministries inquired. The money was short. The search was long.

The tire shop was closed and boarded up, a for sale sign out front. Andy saw it one day walking out the door of Hope’s offices. It was right across the drive. Hope Ministries inquired. The money was short. The search was long.

Then fate—or perhaps something else if you were to ask the people of Wytheville—stepped in, much as it had before. A large donation left behind in an estate arrived, a denizen of Wytheville, her last Pay What You Can, just exactly enough for Hope Community to purchase and renovate the tire shop and slide the doors of that old garage shop up once again.

"That was one of those God wink, spine-tingling moments that said that this project was meant to be."

–Andy Kegley

Only this time when the sliding grind of metal doors hit your ears, it meant hot food instead of a tire rotation, a one meal respite every day for those without means.

And for those with heavier pockets, they could pay just a bit more if they desired—perhaps enough for an extra meal or two or three for their neighbors. This experiment has lasted 3 years. And each year has ended in the black. Enough to keep the experiment going another year. Viability.

"You know when you hear the words Open Door Cafe, you immediately think food. But it’s so much more than that."

–Mike Pugh

And that’s not even the best part. The best part is when no one picks up their food and gets in their cars to eat alone, checking sports scores on their phones or Facebook updates or jumping back on the interstate to get to the next destination.

Instead, at The Open Door Cafe those with tokens in their pockets (a currency for free meals) and those with real metal rattling around in theirs, sit across from one another at tables both indoor and out, in a spirit of community. You can hear stories of births and deaths, the past week’s sermon, updates on job openings, and who scored what against whom in last weekend’s game (baseball in the summer, football in the fall, basketball somewhere in between). The gift of reciprocity hovers in the air among the laughter. And among the laughter, there is one laugh in particular that rises above the drum of it all. That would be Frankie Odum.

Frankie Odum cruises into the ODC once a day by most estimates, always looking forward to that home-cooked meal provided by the volunteers of which she is one herself.

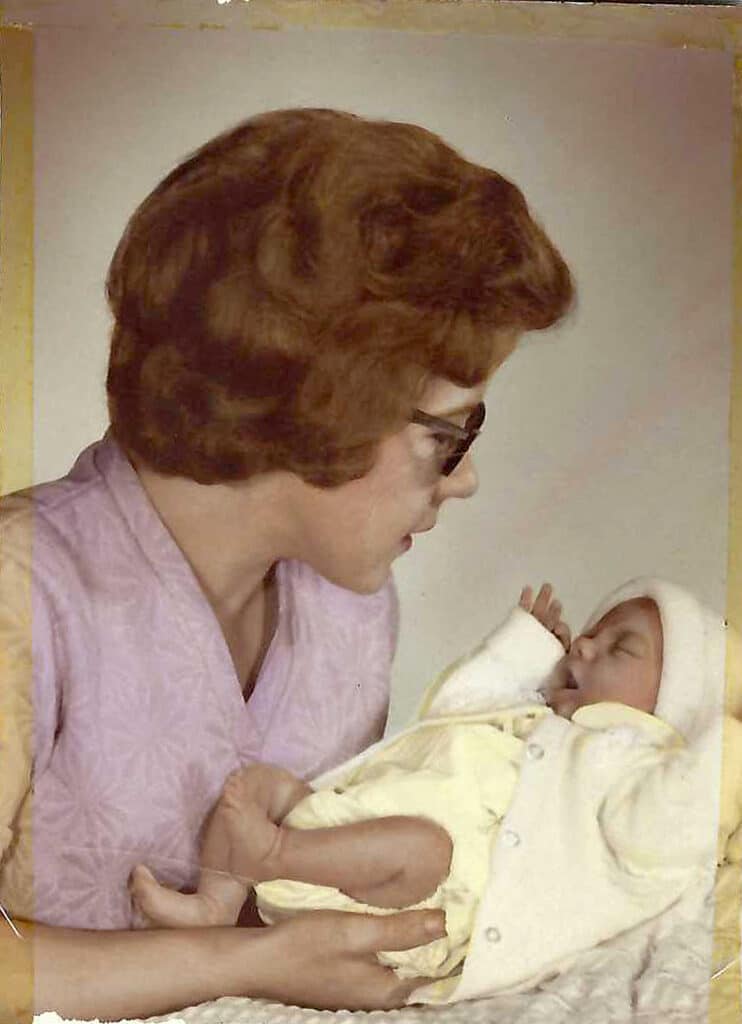

Frankie is a self-described military brat. For all intents and purposes, she had seen a lot of what the world had to offer. Growing up she lived all over, both in America and abroad. And as life crept up on her, in all this din, she heard Wytheville’s call just a few miles from her mother’s birthplace, Cripple Creek. Perhaps it was her mother’s heritage calling. She couldn’t quite put her finger on it, but she went. And she found exactly what she was searching for: a place where time comes off the clock just a hand tick slower than the rest of the world.

Frankie is a self-described military brat. For all intents and purposes, she had seen a lot of what the world had to offer. Growing up she lived all over, both in America and abroad. And as life crept up on her, in all this din, she heard Wytheville’s call just a few miles from her mother’s birthplace, Cripple Creek. Perhaps it was her mother’s heritage calling. She couldn’t quite put her finger on it, but she went. And she found exactly what she was searching for: a place where time comes off the clock just a hand tick slower than the rest of the world.

"I came out to visit my cousin and fell in love with this place. I says I’m moving here. I had forgotten how many shades of green there were."

–Frankie Odum

After losing the use of her legs in a car crash and facing other health-related issues, the community of Wytheville and the Open Door Cafe became a balm every day. As she cruises into the cafe, she high fives just about every person she passes on the way to her table. She does her best to dispense some of the positivity that pervades her life to those who may not yet have the vision to see where it exists in theirs.

She helps however she can. “Can’t work on the line,” she says, “I would just get in the way.” She indicates her wheelchair. “I can’t serve food because, again, I’d just get in the way.” But there’s something she can do, she says. And that thing is making string. String? Yep, string.

She helps however she can. “Can’t work on the line,” she says, “I would just get in the way.” She indicates her wheelchair. “I can’t serve food because, again, I’d just get in the way.” But there’s something she can do, she says. And that thing is making string. String? Yep, string.

Food insecurity stretches across Wytheville. As a result, the Cafe’s volunteers make and ship out over 800 meals each weekend for food-insecure children throughout the valley. Each one of these meals is packaged in paper and bound by twine. And each week, Frankie supplies nearly a thousand pieces of handmade twine crafted at her kitchen table to the Open Door Cafe. “It’s my way of contributing.”

Frankie calls Wytheville home now. Her brother visits. “It’s slow,” he says without passing judgment. Frankie comes to life, pointing out all the little things that a life in the country makes worth living: the neighborly smile, a kind hand for someone in need, all the green a person could ever need, never a moment of loneliness so common in her former city lives.

Right there in that moment, you can see in her eyes the pride and spirit that keeps her here, the bonding strength of her roots, whispering to her to stay until her last days. And her look, with that famous Frankie smile, says she just might.

From among all these stories is a small glimpse of what could be, a slight wresting away of control from fate as to what the future holds, a town and cafe whose values spread beyond the spread, so to speak. And in that small effort to regain some control, you may consider inviting fate to the table, maybe even buy it a meal. Because despite its ambivalence over the millennia, perhaps it has a story worth hearing. And one it wants to tell over a home-cooked meal.

Published 2021