Michael Stegall

Wynne, Arkansas

Gazing out at a patch of field, Michael feels his father’s presence. “I spent a lot of time with him here. Working with the chickens, mending the fences, you know, picking the eggs. And I came to this spot a lot during my troubled periods.” The spot to which Michael returns, sits on the edge of what is now a 40-acre farm where he grows soybeans and a variety of vegetables. And it’s a short walk from the house where he grew up and still lives.

When Michael’s father purchased 80 acres of land in the late 1940s, he did so with an idea that the land itself - with some tools, a tractor, and a lot of hard work - held everything needed to make a stable life for his family.

But in the decades following World War II, the agricultural industry slowly transformed across the nation. Emboldened by a drive for mass production and global trade, an emerging system encouraged farmers to “scale up” by acquiring more land and purchasing more advanced machinery. But because this process significantly increased the costs of operation, farmers like Michael could no longer rely on their own tools and labor.

But in the decades following World War II, the agricultural industry slowly transformed across the nation. Emboldened by a drive for mass production and global trade, an emerging system encouraged farmers to “scale up” by acquiring more land and purchasing more advanced machinery. But because this process significantly increased the costs of operation, farmers like Michael could no longer rely on their own tools and labor.

To remain viable, access to resources like loans and other government subsidies became essential. For most, farming at mass-scale required taking on debt. According to Dewayne Goldmon, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) began to offer programs designed to operate as a “safety net” and provide access to such financial resources.

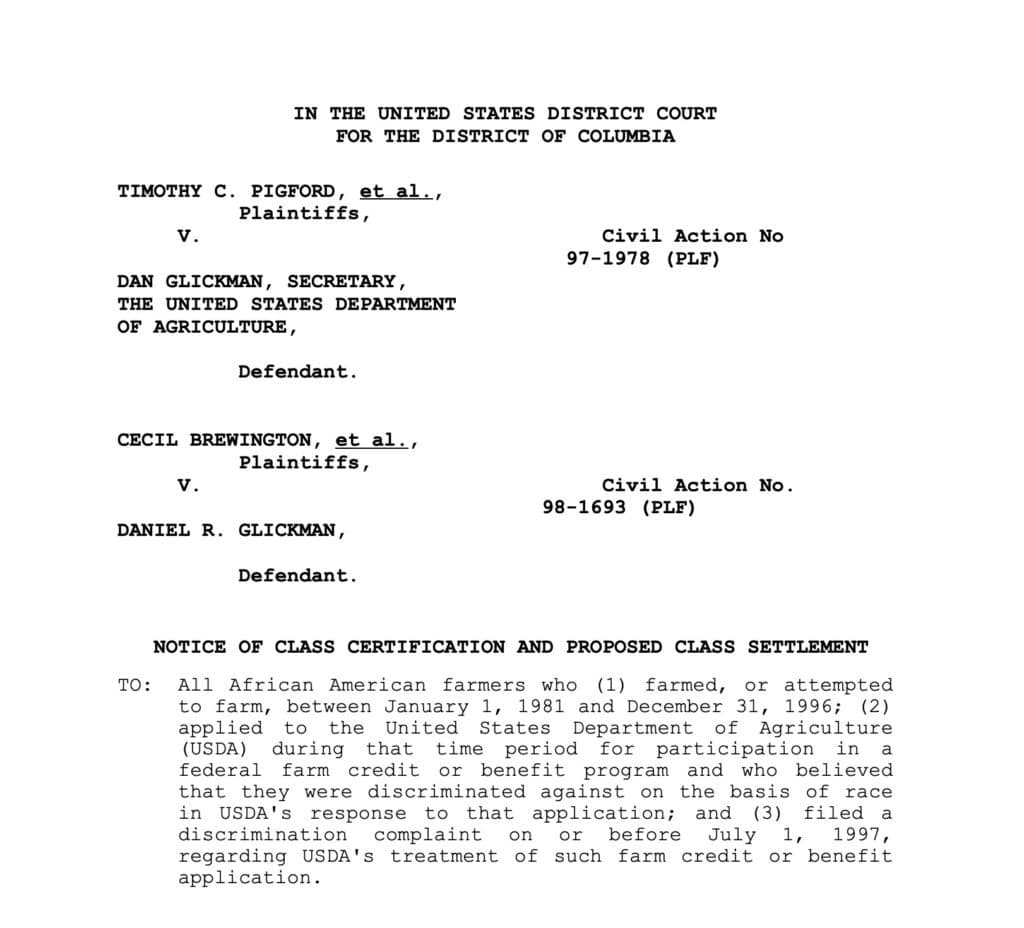

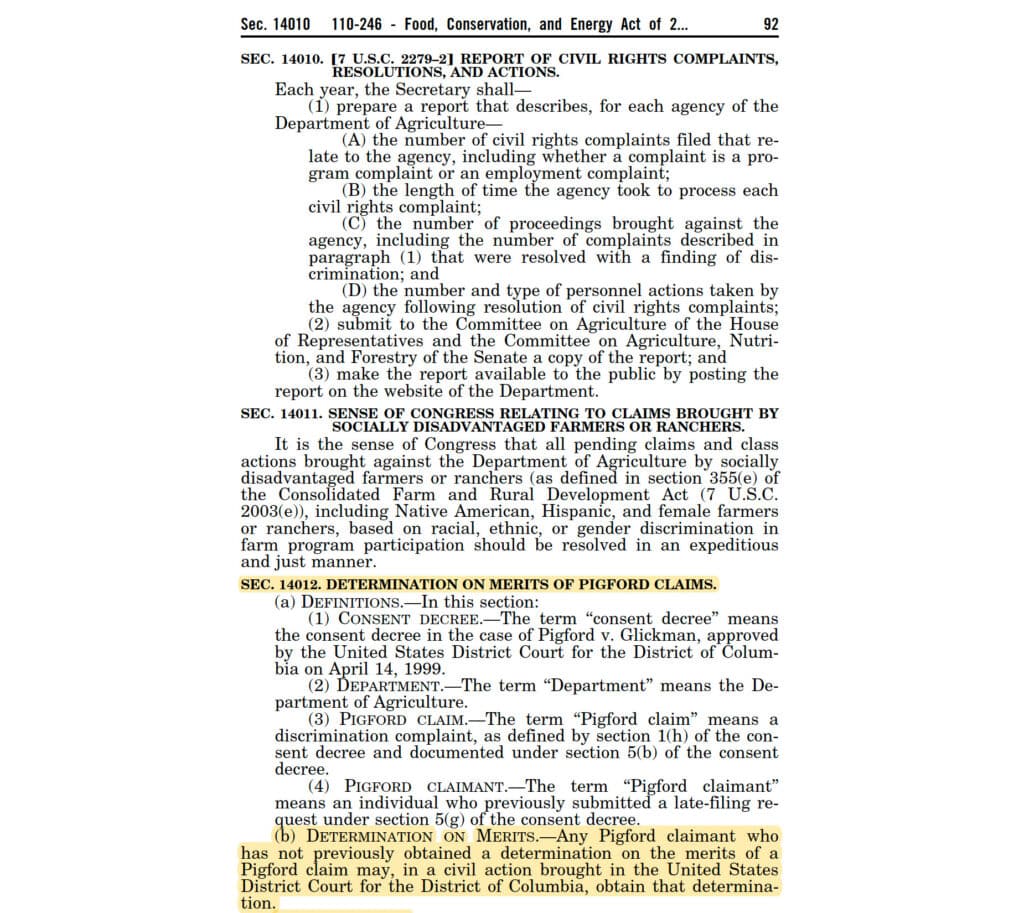

However, between 1948 and 2015, an estimated four million farms disappeared in the United States. And from 1950 to 1969, farmers who identify as Black lost nearly 12 million acres of land. In 1997, Michael was among four hundred Black farmers who filed a class-action lawsuit against the USDA for discriminatory lending practices.

Pigford I, as the case became known, grew in scale as awareness spread among Black farmers throughout the country. Thousands alleged that the USDA treated them unfairly when deciding to allocate price-support loans, disaster payments, "farm ownership" loans, and operating loans; and that the USDA had failed to process subsequent complaints about racialized discrimination from 1981 to 1996.

photo courtesy of Lawrence Lucas

On April 14, 1999 courts ruled in favor of Black farmers. Those with necessary documentation could claim their settlement through two different options. The most widely chosen option provided a monetary settlement of $50,000 plus relief in the form of loan forgiveness and offsets of tax liability. In the end over 22,000 claims were officially filed, far surpassing the originally estimated 2,000. But, it’s estimated that more than 70,000 claims were turned away.

In 2008 legislative language was added to the Farm Bill that enabled more farmers to bring suit and authorized the federal government to negotiate additional settlements. In 2010, settlements for an additional $1.2 billion in claims were reached, in what is known as Pigford II. Congress appropriated the money later that year, and successful claimants received their settlements in 2013.

Pigford et al. v. Glickman was filed in 1997

Denied claims reopened in 2008 Farm Bill

Together these two cases produced one of the largest civil rights settlements in U.S. history. But in a country with a long history of racialized discrimination, questions remain.

When Black farmers were denied loans or received worse loan terms than white farmers, the consequences were devastating. Many Black farmers faced foreclosures, high debt, and the loss of their land and livelihood. As a result of the Pigford cases, many Black farmers received settlements of $50,000 or less. While these settlements were welcomed, most came nowhere close to covering the amount of assets or money lost over time. And in many cases, the settlements didn’t cover the costs of resuming production.

Simultaneously, the Biden administration attempted to include $4 billion of debt forgiveness for Black and other “socially disadvantaged” farmers as part of the American Rescue Plan. These comprehensive recommendations and attempts at institutional reform paint a more hopeful picture. However, they also outline a terrain for significant legal battles, which continue to grow.

The debt forgiveness program was blocked after groups representing white farmers filed lawsuits arguing that the federal government was engaging in “reverse discrimination” by awarding money based on race. And the Biden-Harris administration’s Department of Justice ultimately declined to appeal the court ruling that blocked the program from going into effect. Attempts to redress the effects of past discrimination based on race were blocked in the name of “reverse discrimination.” In effect, this means to prevent racial discrimination in the present, the past can be erased.

But history leaves marks not easily smoothed over. Between 1920 and 1999, 98.1% percent of Black farmers left their profession and 85% of the land owned by Black farmers was lost. In the same period, White identifying farmers collectively saw the number of acres owned grow slightly and their numbers drop by approximately 66%.

But history leaves marks not easily smoothed over. Between 1920 and 1999, 98.1% percent of Black farmers left their profession and 85% of the land owned by Black farmers was lost. In the same period, White identifying farmers collectively saw the number of acres owned grow slightly and their numbers drop by approximately 66%.

In July of 2024, under Section 22007 of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the USDA provided $2 billion in financial assistance to farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners who reported discrimination in farm lending prior to 2021. The Biden-Harris administration announced it has issued payments to eligible applicants.

For thousands of Black farmers like Michael, the past lingers on in the brute lived experience of disproportionately endured debt, loss, and trauma. Michael’s life - like all farmers’ - has been lived through the grounds on which he still stands. But underneath the layers of loss, family memories emerge from each idle tractor and every standing fence post. For Michael, there remains meaning found both in the soil beneath his feet and in the words of his father: “All this. This is something to be proud of. It may not be a lot compared to others, but this is yours so take care of it.”

Published 2024